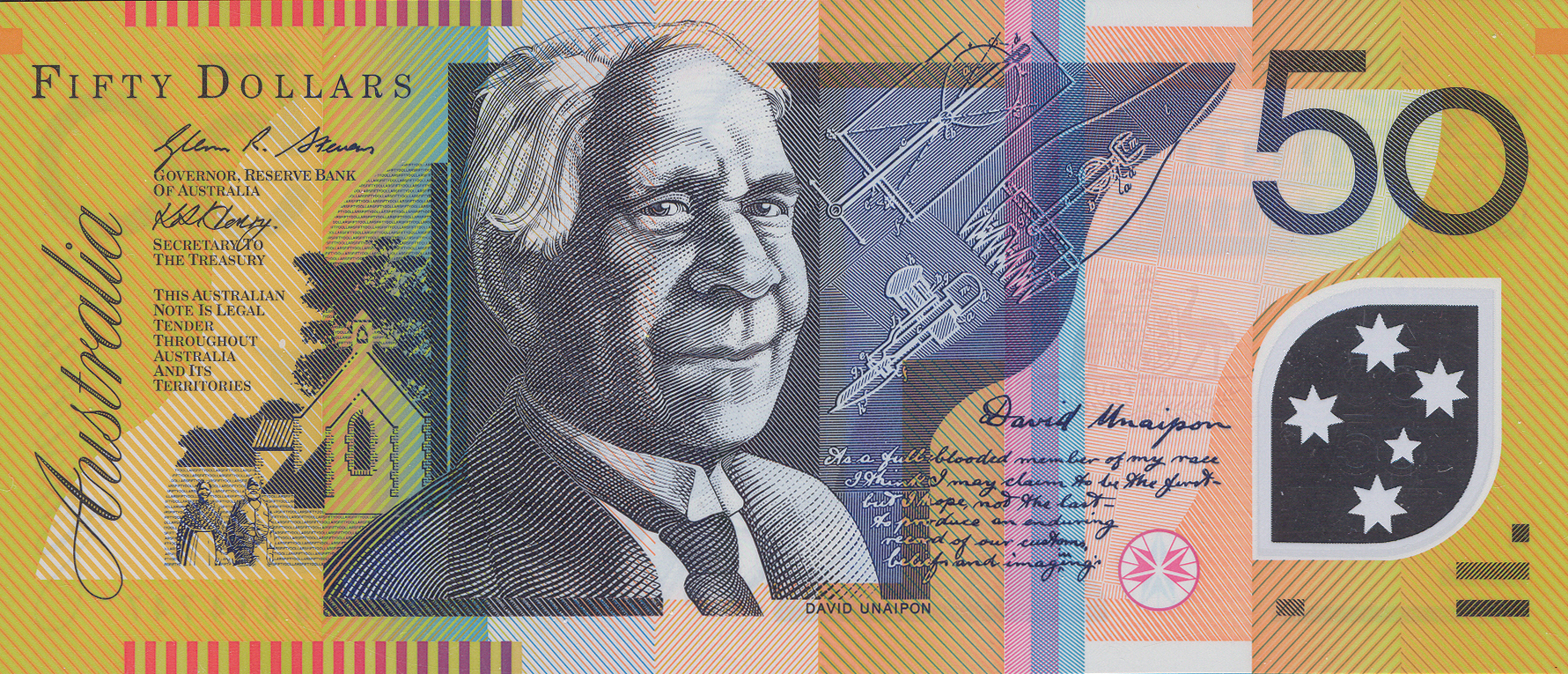

According to a Telegraph article dated 28 November 2008, Allan “Chirpy” Campbell claims the Reserve Bank of Australia gained permission to use the image of celebrated indigenous author and inventor David Unaipon from a woman who was posing as his daughter, and did not obtain authorisation from a genuine family member.

“They jacked this woman up and proclaimed that she is the daughter of my uncle, and when we found out they blocked us and they chucked all the barricades there,” he told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC).

“We are the family, I had to produce my genealogy, I had to produce my documents and documentation, they don’t have to, they just say it, and they accepted it.”

Mr Campbell, 61, travelled to Sydney this week to make his case for compensation to the Reserve Bank.

The bank, which has so far denied Mr Campbell’s demands, refused to comment on the three-hour meeting, but made it known that it believes the appropriate advances to Mr Unaipon’s family were made at the time the note was designed.

However, it is understood that those agreements were verbal and no official document of permission exists.

Mr Campbell, a lifelong campaigner for Aboriginal rights, has said he is willing to take the matter to court to obtain a “fair dinkum settlement”. If successful, he plans to use the $30 million to start a charity for mentally ill children.

“They’ve got to renegotiate this time a proper settlement, not a tea leaf, sugar and flour syndrome, you know,” he said.

“They’ve got no proof, no papers to show she is his daughter.”

David Unaipon was Australia’s first published indigenous author, an inventor and preacher from the Ngarrindjeri people of South Australia.

He held a patent for a sheep shearing mechanism that is depicted beside him on the $50 note.

In his work as a preacher, Mr Unaipon travelled widely and became well-known throughout Australia.

He lectured on Aboriginal legends and customs and also spoke of the need for “sympathetic co-operation” between whites and blacks, and for equal rights for all Australians.

He died in 1967. His image appeared on the $50 note from 1995 when the polymer bill was introduced.

“They jacked this woman up and proclaimed that she is the daughter of my uncle, and when we found out they blocked us and they chucked all the barricades there,” he told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC).

“We are the family, I had to produce my genealogy, I had to produce my documents and documentation, they don’t have to, they just say it, and they accepted it.”

Mr Campbell, 61, travelled to Sydney this week to make his case for compensation to the Reserve Bank.

The bank, which has so far denied Mr Campbell’s demands, refused to comment on the three-hour meeting, but made it known that it believes the appropriate advances to Mr Unaipon’s family were made at the time the note was designed.

However, it is understood that those agreements were verbal and no official document of permission exists.

Mr Campbell, a lifelong campaigner for Aboriginal rights, has said he is willing to take the matter to court to obtain a “fair dinkum settlement”. If successful, he plans to use the $30 million to start a charity for mentally ill children.

“They’ve got to renegotiate this time a proper settlement, not a tea leaf, sugar and flour syndrome, you know,” he said.

“They’ve got no proof, no papers to show she is his daughter.”

David Unaipon was Australia’s first published indigenous author, an inventor and preacher from the Ngarrindjeri people of South Australia.

He held a patent for a sheep shearing mechanism that is depicted beside him on the $50 note.

In his work as a preacher, Mr Unaipon travelled widely and became well-known throughout Australia.

He lectured on Aboriginal legends and customs and also spoke of the need for “sympathetic co-operation” between whites and blacks, and for equal rights for all Australians.

He died in 1967. His image appeared on the $50 note from 1995 when the polymer bill was introduced.

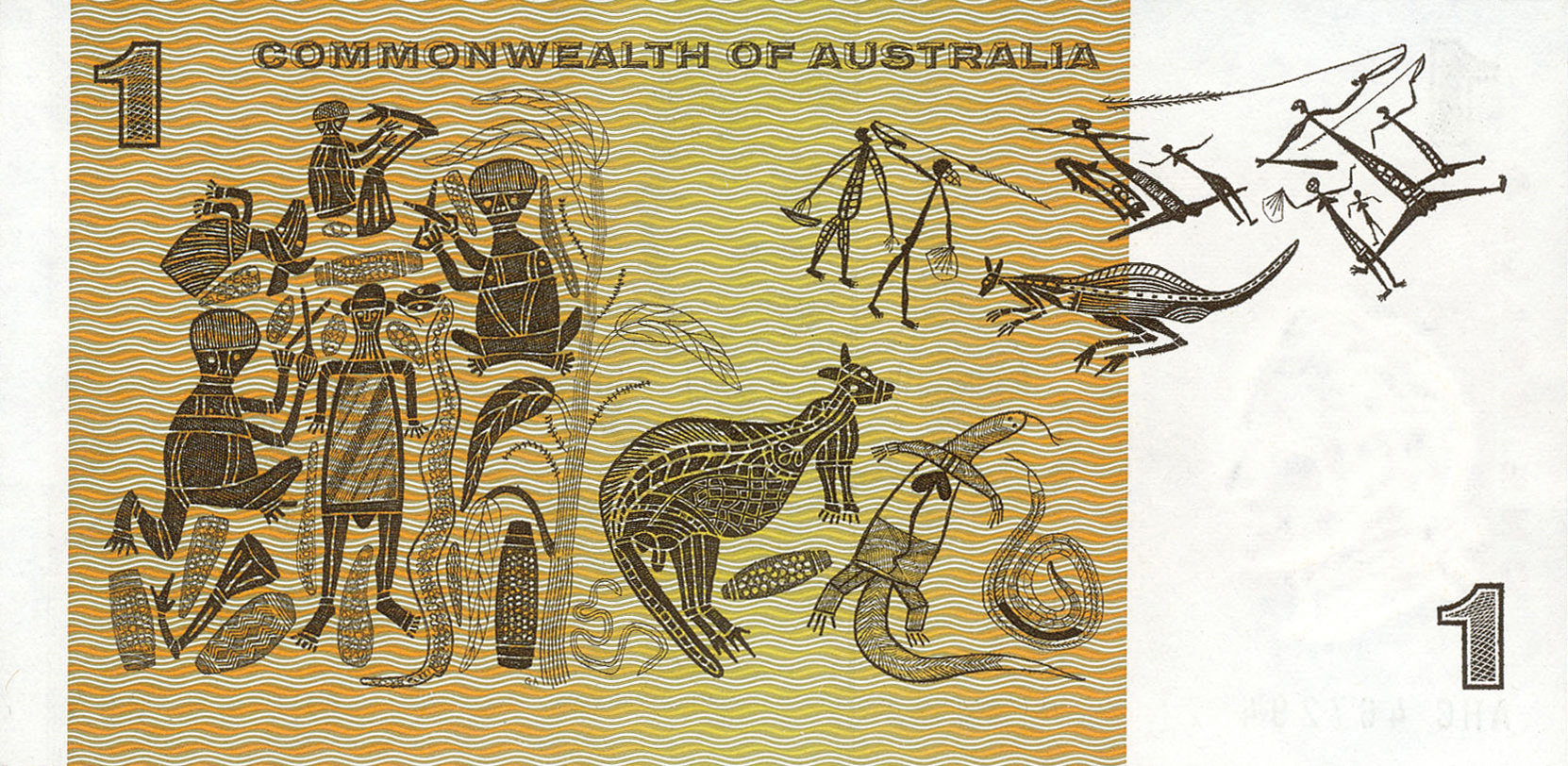

The Unaipon case echoes the use, in 1966, of a bark painting by Arnhem Land artist David Malangi on the $1 note. It later emerged the artwork was reproduced without permission. Mr Malangi was compensated $1,000, a fishing kit and a silver medal.